Photographer of the Year

Libuše Jarcovjáková

“The director of the Arles festival offered me space for a big exhibition. I’ve been waiting for such a break for fifty years, my whole life. The entire time I was convinced I was a photographer, but no one cared.” These are the opening lines of last year’s film I’m Not Everything I Want to Be, which confirmed Libuše Jarcovjáková as an international star. Although her path to stardom in her home country had a slow start, picking up towards 2010 and onward, it was only the international success of her presentation in France in 2019 that really confirmed her recognition. Today, Jarcovjáková’s work is exhibited across Europe, she is the leading figure behind a successful publishing house, and her presentation at the Berlinale in Karlovy Vary presented her to the wider public as a multifaceted, inspiring heroine whose impact reaches well beyond the art scene. When it came to the task of finding nominees for this year’s Czech Grand Design Awards, it was hard to imagine her not receiving a prize; the only question was whether it would be the Hall of Fame, Photographer of the Year, or Discovery of the Year…

Jarcovjáková’s life is full of such turns of fortune. She has always been hip, but her life story has only come into its own in recent years. She started taking her first antidepressants in the mid-1970s; even though she is 73 now, she remains more attuned to the emotional spectrum of today’s twenty-somethings than the crustiness of her peers. Even in the 60s, she was burning through roll after roll of film with the appetite of someone who just received their first iPhone; she has had an Instagram account for ten years but it seems her pics were made for it since before the White Album came out. The photographic series documenting the passing of her mother could just as well have been shot with a Hipstamatic filter. Much of her sensibility and style would only come into vogue decades later: the diary-like documentation of one’s own emotional experiences; a soft spot for minorities; polyamory; bisexuality; bashfulness in social contact contrasting with her nakedness before the camera; identity as performance and photography as a tool for endless search and creation; imperfection as a mark of authenticity and the favoring of candid moments over ideal form; (self)care; doubting oneself while being convinced of her right to success; individualism; the autonomy and solitude of the nomad life; a fundamental rejection of both the “woman’s role” and the servant status of a person born in a Soviet satellite… The combination of frivolity, determination and the self-destructive assuredness of her own worth have always made her unpalatable to the gatekeepers and guardians of the canon.

Although Jarcovjáková did achieve some success decades ago. In the 1980s, she went to Tokyo, where her blasé approach to documenting luxury – a practice since made famous by people such as Jürgen Teller or Martin Parr – afforded her a solid career. “Everyone finds my idea of throwing a brand-name dress shirt into the sand very original,” she says in the film, paraphrasing her diaries from 1986. And she writes home one sentence which, forty years later, is posted by Lena Knapp in Paris (and cited elsewhere in this yearbook). “Dear mom, I am dead tired but happy,” she writes. “My photographs have been published by prestigious magazines like Edge, Brutus, Popeye… Wish me luck tomorrow, I am shooting portraits of Rei Kawakubo…”

Like many from the generation growing up around 1968, Jarcovjáková (*1952) could not study due to her origins. She knew she wanted to become a photographer since she was sixteen, but she passed her four years of waiting for admission to FAMU working night shifts at the printers’ and in pubs – since she didn’t have a class profile, she decided to create one. Even before she got in on her third try, she had already had two abortions and the night life called to her louder than FAMU’s elitist cliques. And she never stopped photographing. Ever.

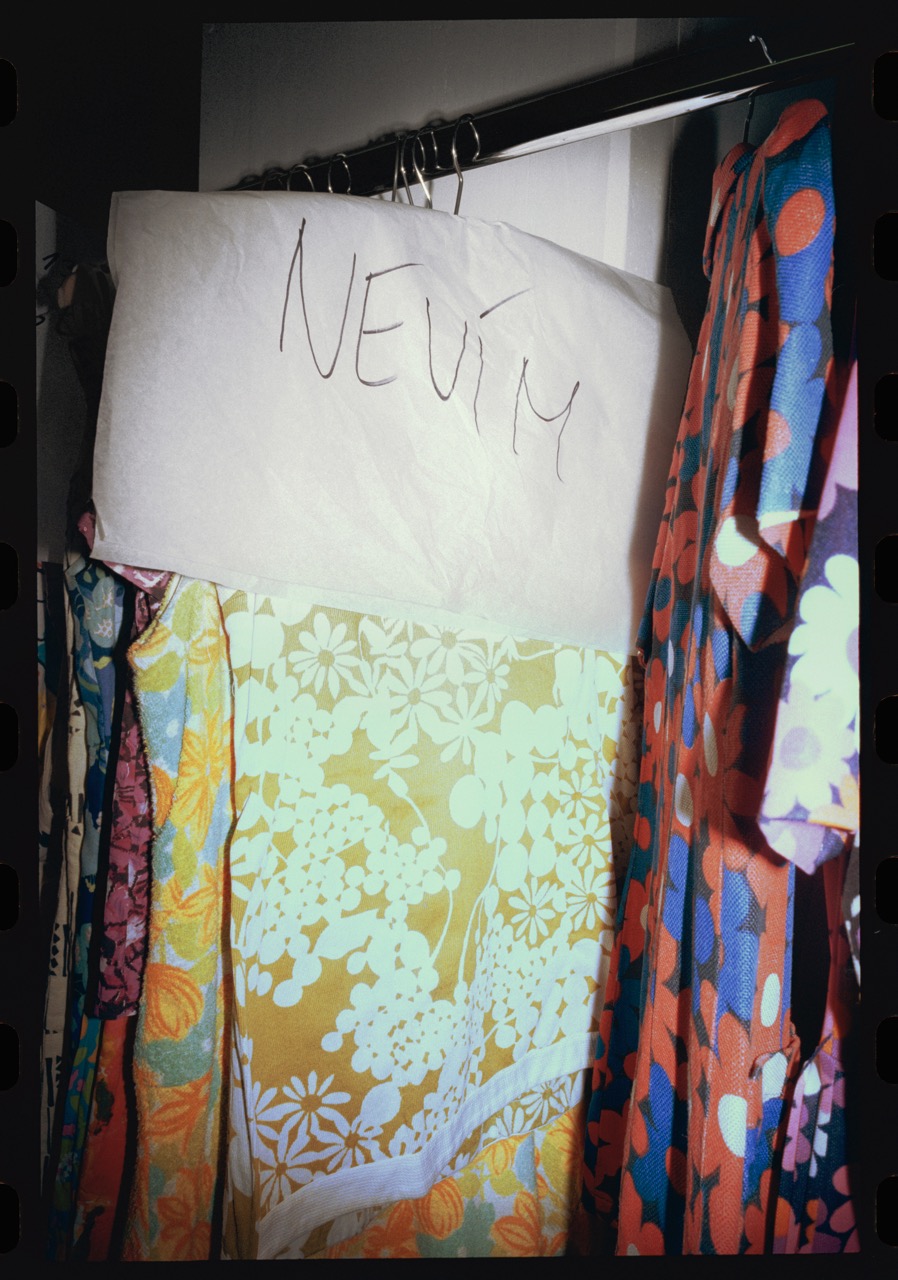

She photographed the Roma, the Vietnamese and the Cubans she was teaching Czech, but most importantly herself. Her mornings after, lovers of both sexes, beds, just her. She first left Czechoslovakia in 1979, flying to Japan for two months but almost ended up living on the street. After her return, the authorities confiscated her passport. She found solace in the T-Club, an unofficial gay bar near Jungmannovo square. Yet her curiosity about the wider world never left her and when a fake wedding provided her with an opportunity to fly the coop, she moved to West Berlin in 1985. She returned to Japan a year later with a good portfolio and soon made her name shooting for stylish magazines.

But again, “no one cared.” In a sense, she didn’t either. It is a paradox that Jarcovjáková is the first photographer inaugurated into the Czech Grand Design Awards’ Hall of Fame for applied art, because she seldom does commission work. Some examples include the campaign for the National Theater, photographs for the book Mami, miluju, the Projektil33 book focusing on architecture or Vogue CS. She left Japan because she was homesick and didn’t have visa, preferring to work as a maid in Berlin. “People like my work, but I am not very happy with it. The photos contain very little of myself in them. This work could earn me a good living, but it is all so commercial. Is this what I want?” It is generally the case in applied arts that the people who feel like outsiders go on to produce the most interesting visuals. Commercial work can become tedious but brings quick earnings, while the path to original work is paved with uncertainty. “Although I make my living washing stairs, I’m still a photographer. Maybe even more so.” Jarcovjáková’s story in many ways asks questions about who determines one’s identity – is it the guardians of the discourse or rather your own convictions?

The Japanese and Ester Krumbachová (who was a friend of her mother’s), were the only ones who supported her during her career’s early stages. Yet she never stopped shooting. Ever. “Koudelka is the best at photographing these things, no one can do it like him,” they told her in school. But those in Koudelka’s photographs, her Roma lived in the now, in cities, and listened to LPs of Elvis and Tom Jones. Much like in her images of laborers and pub patrons, Jarcovjáková does not emphasize the difference in their time and place but rather their closeness. Instead of making poverty into an ornament and documenting the forgotten or arrested time as some imaginary yesterday, she accents flow and confluence. “I am fascinated by how they live in the total present, as if tomorrow never existed. We are kindred souls, as they too have been disenfranchised in their own country.”

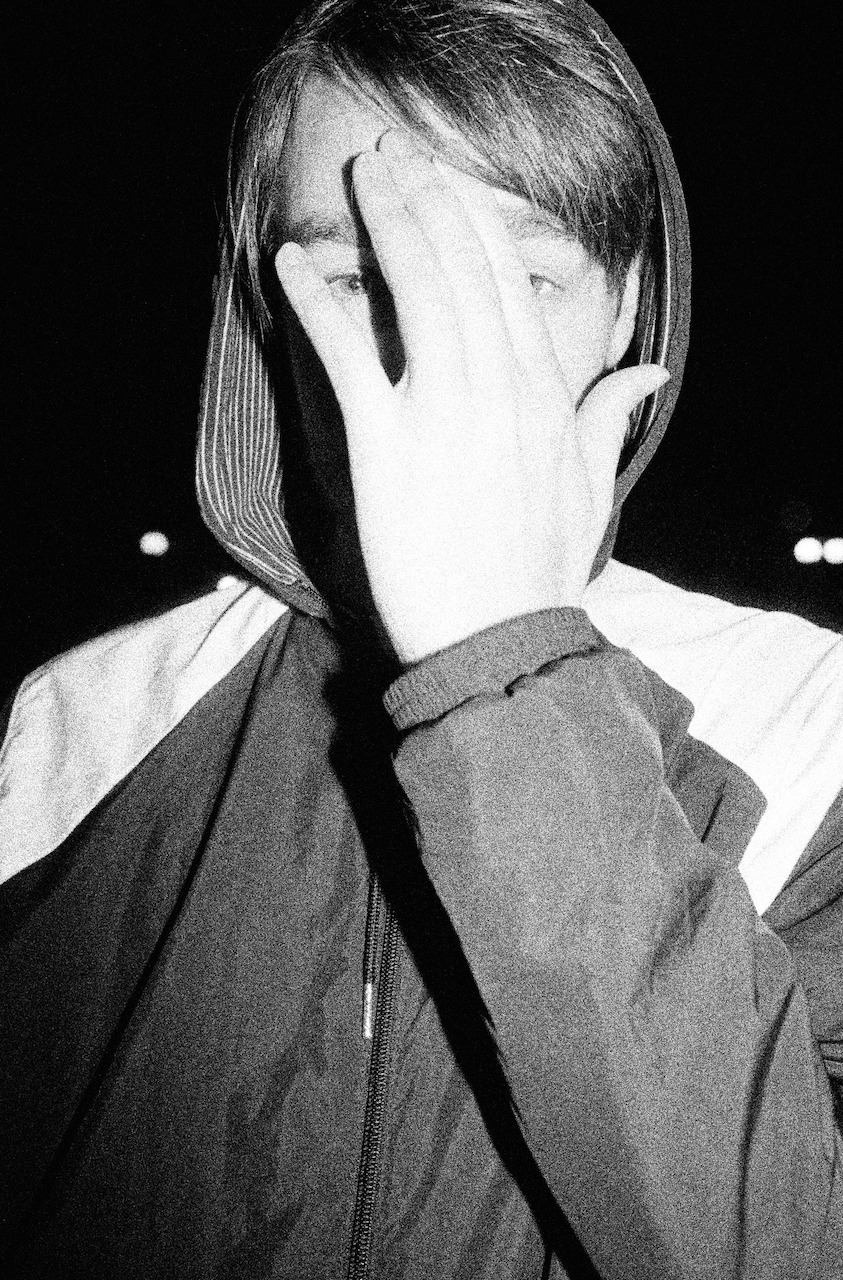

After all, these photographs never believed in a single moment of truth, in being concentrated in a single point, there is nothing definitive about them. Much like explorations of the mutability of the female body, of its mind and roles, the images don’t struggle against the passing line of time but are enmeshed in it. It is fascinating just how many individual captivating images Jarcovjáková managed to take – especially considering that she was often shooting in states beyond rational control. Her work isn’t about solitaire images but rather about visual, shimmering clusters. It shows hard knocks and falls, injuries and desires, and adopts a series of perspectives rather than individual views. Jarcovjáková shoots from the hip, offering uncensored images of intimacy and sentimentality. Her spontaneous use of photography as a tool of life and the formation of the self was a cast glove to the era’s predominant idea that a true photograph comprises an absolute product, untethered from its surrounding conditions and unstrung from any umbilical cords. Her work stands against the ideal that a photograph must contain the condensation of reason, that it must be an ideal machine, complete and immutable – perhaps as in the works of Josef Koudelka, who was a professional engineer throughout his life and is currently Jarcovjáková’s neighbor.

Instead, we get the passionate flow of tears and emotions, views of her toes across her chest, the doubt and piss on the pavement. “I look into the mirror for hours on end, wondering whether it is still me… I need positive proof that I am here, that I am alive, that I haven’t disappeared.” Pics or it didn’t happen. While others imposed their personal, incontrovertible ego on the work, Jarcovjáková’s images show the ego in process and formulated with the aid of photography. She is certainly not an innocent bystander in all this; she is a seasoned artist who ultimately frames the image and decides what to present. Yet instead making her image and personal vision fixed, Jarcovjáková is always asking who she is – and prompts others to do the same. Various people have borrowed her camera eye, and today her work invites emulation by some of the most progressive photographers of all generations.

When she returned to Prague from Berlin in 1990, no one cared about Jarcovjáková or Comme des Garçons. She spent the next twenty years as a “high school teacher.” She never had children of her own – “Why should the life of a woman be defined by motherhood? Why can’t I live the way I want to?” – but she has been teaching for over thirty years, first at Hellichova College of Graphics and Secondary Technical School (1992–2014, head of the photography department), and nowadays at Ladislav Sutnar Faculty of Design and Art, where she held the position of assistant from 2015 until 2022, when she became the head. Her students consider her an inspiring teacher who brings magazines for them to read under the desk during class and knows more about the goings-on in the West than the cramped-up Czech documentary tradition. While the Master-apprentice system – where larger-than-life figures knead their followers in their own image – has been alive and well, Jarcovjáková always supported the individual passions of numerous generations of students, including laureates of the Czech Grand Design Awards like Salim Issa, Štěpánka Stein and Adam Holý.

In an era when society clearly determined one’s social status, no one cared much about questioning who they might become or how many faces they wear. But with the increased availability of cameras, photography became one of the main tools for putting this newfound possibility to practice. Early experimentation led to a state of constant conflict with the era’s social limits – the narrowly defined role of women, sexual minorities, urban youth, artists, foreigners or emigrants – and running with that potential, they honed it to an art form. As the daughter of two painters, Jarcovjáková embodies the marriage of the highbrow and the lowbrow in the tradition of Shakespeare’s prince Hal – a character who leaves his affluent origins to engage in rebellious excursions into the underworld. She was never a snob in choosing her company, topics or technique – she enjoys photographing with an automatic camera or even a phone. She takes to the streets with erudition, and even the photographs from her wild years show a strange sense of sophistication. Her question “Why couldn’t I live the way I want to?” speaks just as much to her feelings of entitlement as to her willingness to suffer for it. Her images show a balanced sense of experience and life, a guided contingency, the artist’s appreciation of flow and distaste for overdetermination – in this sense, they mirror her biography.

Jarcovjáková never let herself be normalized, living as if the lethargy of Czechoslovak socialism never existed, but she also never indulged in any established escape strategies. She was not befriending the dissidents, did not spend her weekends at the cottage, did not give birth to Husák’s children, didn’t crawl under any barbed wire. Much like many other world-travelers, she did not fit in with Prague’s photographic circles nor the art establishment, remaining convinced of herself and her own worth. But the question of who she is and where she belongs remains something she wakes up to every day. And through it all, photography served as an analytical tool and a source of support in exploring and creating a sense of her own self, her own self-image. It confirmed that she is not just taking photographs but that she indeed is a photographer. And now, after growing her audience, she can get others behind her vision too. “Life passes too quickly to understand anything. Photographing is the only way of survival.”

Michal Nanoru